As a student at the Norfolk Chamber Music Festival New Music workshop, I remember vividly being advised by virtuoso pianist Lisa Moore not to engage in the “politics of intonation.” Fixed pitch instrumentalists, she argued, should keep their mouths shut.

I am ignoring her advice to go domain-specific, addressing the topic of tuning timpani.

Part 1:

Tuning a single note

Tuning a diad

Tuning in sequence

Part II

Why are timpani so hard to tune?

Head Clearing

Part I

String players tune the strings of their instrument in consort with one another. The G string on a Cello is generally tuned in relation to the C string, creating a sympathetic/acoustic resonance that enhances the sound of the instrument.

Timpanists should do the same.

Timpani are much of the time harmonic instruments. We should tune the drums in sympathy with one another, in a manner that maximizes the impact of acoustic resonance. This makes the tuning faster, more facile, and more applicable to a number of musical situations.

Tuning a single note: Matching Pitch

I know I said I would focus on harmonic tuning, but one has to start somewhere, right?

First, develop the skill of matching pitch. Use a tone generator to create a pitch in the same octave, and match it first by singing, and then on the drum. Most tuning forks are a few octaves above the pitch you’ll actually be tuning on the timpani. Starting with an actual unison, rather than an octave-displaced tone, is key.

As you approach unison, you will hear beats slowing and eventually eliminating as you reach enharmonicity. The beats (subtle pulsations of sonic energy) are phase cancellations from the wave forms being close to one another. Each beat per second is approximately a cent. Repeat. Then repeat again…

While away from instruments, I like to use the InTune app.

Pro tip: the best way to get better at matching pitch is to work on clearing heads. Much the same way that studying microtonality makes a minor second feel infinitely large, clearing timpani heads—working to make sure each tension rod is the pitch—sensitizes our ears.

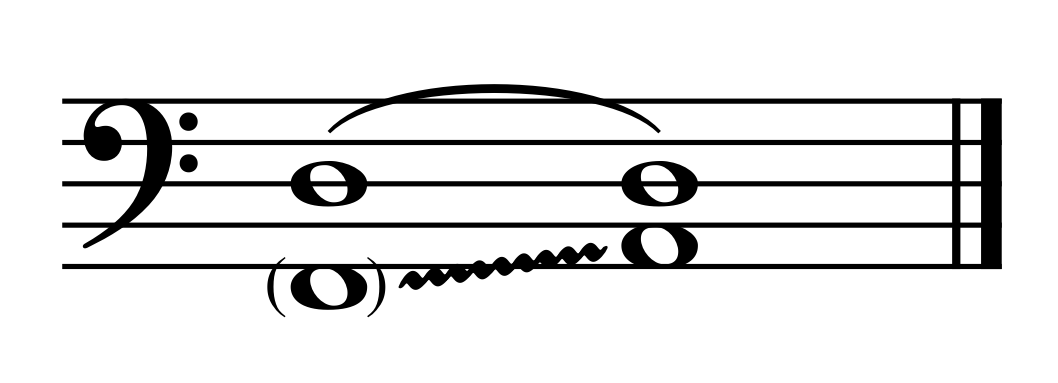

Tuning a diad: Glissando

Our goal: a perfect D and A. Very helpful notes for 18th and 19th century repertoire!

Set one pitch: start with D because in this case, it’s the tonic note

To tune the 2nd pitch (A), tune the 29” drum lower than an A (start around F).

Strike both drums at the same time: this is best with a soft mallet and loud enough to produce enough sound to undertake the glissando described below. Later, flick the drums to do this more discreetly.

Slowly gliss the drum to be tuned up until it reaches the desired pitch:

As you come closer, you will hear the following:

Close to the right note: beating gradually slows

Right pitch: no beating.

Too narrow: beating increases.

One can test if the drums are in tune by hitting one drum and then quickly muting it. If the other drum resonates sympathetically, you’ve done it! Tuning this way ameliorates or at least minimizes the impact of unclear timpani heads by focusing on resultant harmonics rather than hoping that fundamentals and all related partials are in tune.

Tendencies

Theoretically, timpani are just-intonation instruments, capable of slip-sliding anywhere they please. You might notice, then, that some intervals will be more “in tune” by being slightly out of tune.

4ths will sound better when narrow

5ths will sound better wide

Major 3rds should be slightly wide

Minor 3rds should be slightly narrow

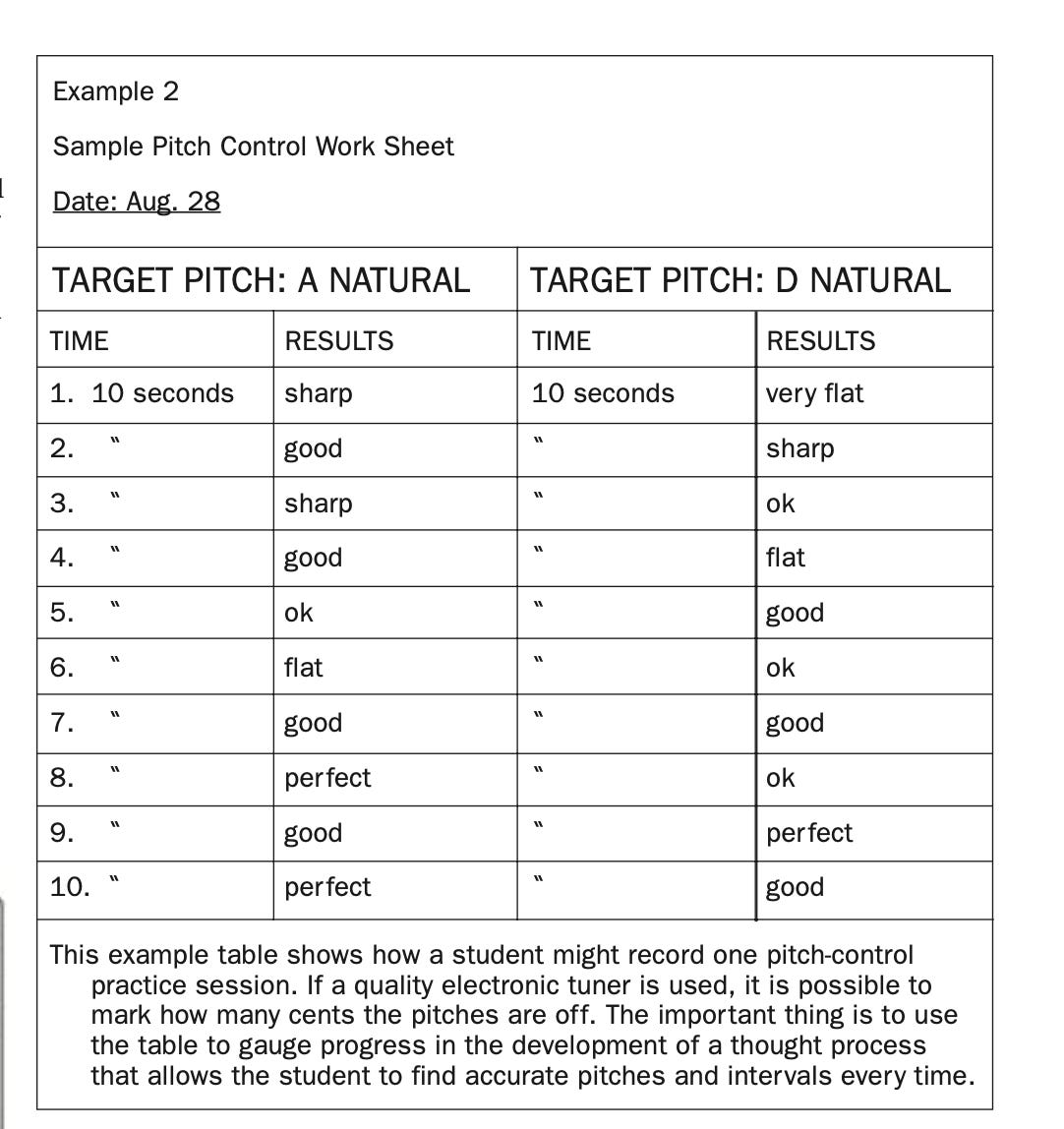

I could imagine an astute student creating a worksheet where they tune 20 A’s in a row, tracking their progress and learning their tendencies. Then, 20 A/D diads. No need to imagine: Christopher Deane outlines exactly such an approach in a Percussive Notes article here:1

Over time, one will improve!

A Timpani Tuning Journey

Next, tackle doing this for… other pitches (gasp!). To assist, I wrote a worksheet. The mission is to move around a set of drums, tuning only 4ths and 5ths, to maximize sympathetic resonance as we move across a pitch landscape.

Instructions

Do this in time if you can

Tune to the next interval using the practice described above, forgoing dropping the drum to its lowest setting and rather moving from the initial pitch to the desired pitch. In m. 2, flick or hit the drums together, and gliss from D to E on the 26” drum.

Tuning down: in measure 4, E moves down to D. Descending intonation is best facilitated by tuning the drum below the needed pitch, finding the pitch by moving upward. It’s easier to hear this way, and it helps with the mechanics of the drums: if one hits the drum after the pitch has been lowered, most drums will have a tendency to lower further. The x on the downbeat indicates to mute the drum before tuning down.

See you next time!

Christopher Deane, “Pitch Control for Timpani,” Percusive Notes 42, no. 3 (2004): 47–50.