Last time I shared some ideas for tuning timpani.

Today, I wanted to share some ideas for getting timpani in tune with themselves, through clearing timpani heads.

But first, I wanted to share some thoughts on WHY timpani are so difficult to tune.

Why are timpani so hard to tune?

There are a number of issues obfuscating the tuning of timpani.

A. Percussionists/Timpanists Themselves

As such, percussionists tend to be less sensitized to the nuances of pitch and more attuned to timbre. Like pianists, percussionists most of the time play fixed-pitch instruments: we’re not tuning our marimbas and vibraphones ourselves. Tuning keyboard percussion instruments is quite a challenge and, despite many amazing advancements in recent years, pitch and overtone clarity are not perfect. Minor seconds are not as bracing on a marimba as they are on a cello, and fourths and fifths don’t ring with the same clarity as they do on a piano. Don’t get us started on thirds: owing to the lower note’s overtone lying somewhere between a major and minor 10th, minor keys aren’t as mournful as they could be. If one hits the lowest C on a marimba, one overtone is generally somewhere between a major and minor 10th above it. While this has inspired some amazing music—the first and last movements of Tonia Ko’s Blue Skin of the Sea come to mind—it does mean that percussionists are often locked into fixed pitch worlds where “in tune” is not really in tune.

NB: This has changed dramatically in my lifetime, and I anticipate marimba tuning to advance even more.

B. The Fundamental is Not the Most Prominent Pitch

Timpani are one of the few instruments whose fundamental pitch is not the loudest overtone heard.

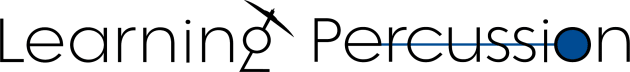

ACTUALLY, the true fundamental of a timpano is usually an octave below the first pitch we hear well. Here’s an outline of the overtones of a timpano tuned to C

Unless the drum is clear, those upper partials will give misleading information on the drum’s fundamental, and be louder than the fundamental and/or “principal tone”

Side Quest: Sympathetic Resonance

These overtones do have a powerful benefit: sympathetic resonance, which I touched upon last week.

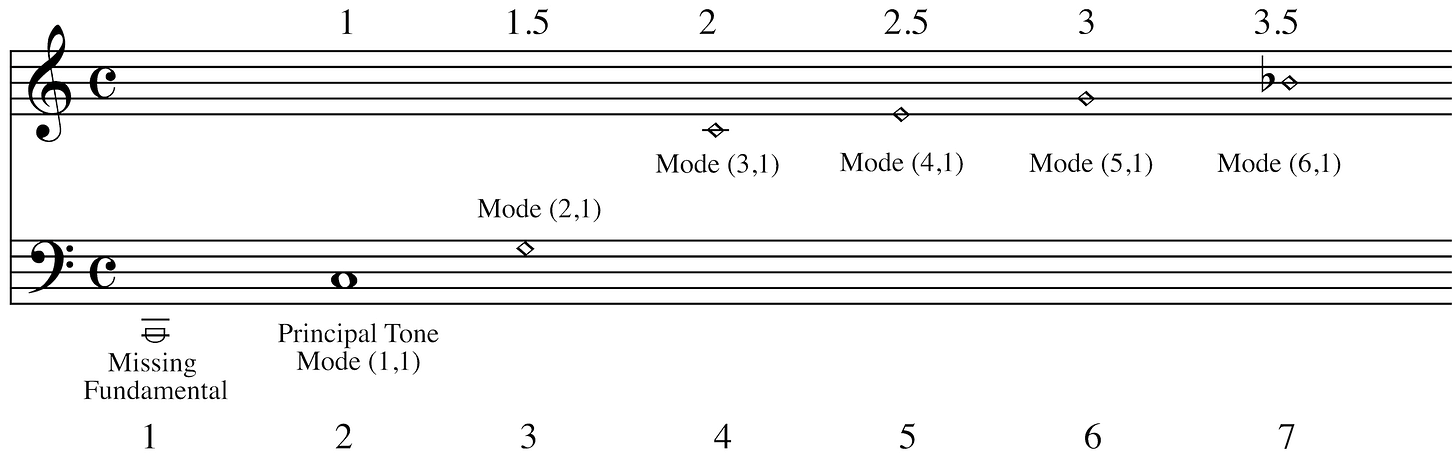

Why is there sympathetic resonance between drums tuned to octaves, fourths, or fifths? Because even if the fundamental pitch is not the same, overtones from one drum match overtones from the other drum. Here’s an example of how, with a perfect fourth (C/F), the 4th partial of the C ( C ) is the same as the third partial of the F ( also C!). With a perfect fifth (C/G), there are two shared overtones.

C. Right Pitch, Wrong Octave:

When timpanists “match” pitch with an A440 tuning fork, I feel like Inigo Montoya from The Princess Bride.

Yes, your fork is an A, but it’s not the same A you’re tuning. The notion that timpanists are “matching pitch” when using a tuning fork is flawed. The fundamental pitch of timpani is often obscured and often out of tune with itself. That alone would make it difficult to hear and match. We make things more difficult by tuning with an A440 fork, when most of the time the A we are tuning is 110 hz. Very different!

Also, octaves are social constructs; fixed-pitch instruments stretch octaves; and just-intonation instruments don’t: octaves are part of the politics of intonation, whether you want them to be or not! I’ve had good success using a set of chromatic tuning forks: when I first tried these as a student, tuning a C was epiphanic.

D. Tuning Ahead of the Ensemble

In orchestras, timpanists changing pitch are often tuning to a harmonic location before the orchestra’s arrival. Trying to tune an E-flat while the orchestra is in E-flat major is tough. Doing it while the group is in D major is asking for trouble. I remember Tim Adams offering some tips for this type of harmonic anticipation when I attended the Cloyd Duff seminar: look for common or enharmonic pitches occurring before the arrival point, and (more simply) just practice tuning ½ steps away from key areas.

E. Heads are Out of Clear

If a drum is not in tune with itself, tuning to another instrument is all but impossible. What do I mean by in tune with itself?

When all the tension rods on a drum are tuned to the same pitch, the drum has a clear fundamental pitch that sings immediately. Overtones are more orderly, facilitating sympathetic resonance between drums.

More importantly, the drum is the same pitch when played softly and loudly. While mechanical issues complicate pitch at loud dynamics (when a drum is played loudly at the top of its range, the pitch will be flat, and when played fortissimo at the bottom of its range, it will go sharp), in general, a “clear” drumhead maintains its pitch at different dynamics and in different beating spots.

When all the tension rods are not the same pitch, the drum’s fundamental is obscured, and overtones include significant beating. More importantly, localized pitch (pitch at a single spot on the drum) is different than general pitch, the pitch across the entire head. This discrepancy creates frustrating distinctions between sounding pitch at various dynamics. If the drum head has a notable flat spot, for example, the sounding pitch of the drum at a loud dynamic will be lower than at a soft dynamic, with a glissando between the “sounding” and “natural” pitches befitting the severity of the imbalance.

On calf heads, life is easier. Calf’s ability to stretch itself means the head generally does most of the clearing itself, with the player left to fine-tune. Likewise, calf’s preponderance of fundamental pitch compared to overtones means that the fine-tuning decisions made while clearing heads are easier.

Even if the player has immaculate relative pitch, an out-of-clear head flummoxes intonation.

It stands to reason, then, that the astute percussionist should work to eliminate as many of these issues as possible, beginning with the mechanical.

How? Clearing heads.

A Clear, Well-Lighted Place

Head clearing is the single most important activity a timpanist can undertake to improve their sound. Having each tension rod tuned to exactly the same pitch eliminates a lot of downstream issues: the pitch is the same at soft and loud dynamics, the drum resonates clearly, the pitch comes immediately, etc.

Much ink has been spilled on the topic of how to ensure each tension rod is tuned to exactly the same pitch. Below is the technique I use, which I learned from Tom Freer, who learned it from Cloyd Duff. I’ve found it reduces choice and focuses on verifiable action, and works well on plastic heads.

Rather than going around each tension rod, we do the following:

Compare the difference between the localized pitch at the playing area and the pitch of the entire drumhead

Make a hypothesis about which tension rod is too tight or too loose

Make an adjustment

Check the adjustment, and if the sound of the drum is improved, move on.

Here’s the procedure:

Find a quiet space.

Mute the other drums to reduce sympathetic resonance.

Tune the drum to a medium-low range, which minimizes the impact of mechanical flex on the pitch of the head.

32”: F

29”: A

26”: C

23” F

Put a mute in the center of the drumhead to cut down on overtones.

Hit the drum softly with a hard mallet in the playing area. Try to pick out the lowest fundamental note you can, trying to ignore both timbre and upper overtones. This is easiest to do with your head close to the drum.

Hit the drum loudly.

Soft stroke = pitch of the entire drumhead.

Loud stroke = more emphasis on the falseness of pitch, emphasizing localized pitch. Playing loudly will reveal how the head is out of tune with itself, with an emphasis on the area in the primary playing channel.

Make an adjustment, moving one tension rod by a quarter or a half turn. Tiny adjustments don’t really move the threads on timpani.

Hit the drum loudly again and assess whether your change made a difference. If so, move on! If not, reverse the change.

Repeat on each drum, striving for one change per drum. Our ears tire very quickly from this focused listening, so don’t spend too long on it and don’t make more than one change per drum.

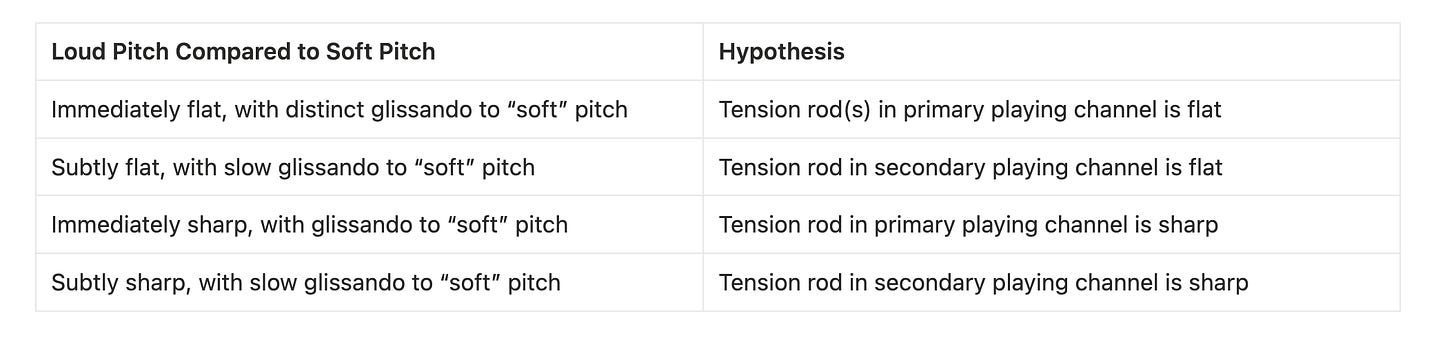

Options:

The primary playing channel is the 2 tension rods surrounding your beating spot, and the 2 tension rods immediately across from them. Why? Timpani heads vibrate like infinite strings, with waves moving from one tension rod to its opposite, and every diameter around the head. There are strong connections between tension rods and their opposites, and often these relationships are more impactful than those between adjacent tension rods!

There are plenty of other methods for clearing heads. One alternative: if the loud sound is immediately sharper than the soft sound, RAISE a tension rod in the secondary playing channel. The most important thing is to create constraints on your work, make hypotheses that are easily verifiable, and move quickly to maximize intuition.

Another Chart?!?!?!

Clear heads are of primary importance as a timpanist. Without them, you can’t adequately judge your intonation and can't really assess sound quality. As such, head clearing should be a part of your work as a timpanist every time you play the instrument. Clearing also has several downstream benefits:

It’s meditative, providing a gentle patch into focused musical work

It enhances intonation more broadly. As I mentioned last time, a half-step starts to sound mighty large when one has been debating single cents

Helps with tuning on other instruments. My snare drum tuning improved immensely once I started approaching it with the same rigor with which I cleared timpani heads.

But, on shared instruments, keeping track of who changes what can be challenging, especially when (not if) someone makes a mistake.

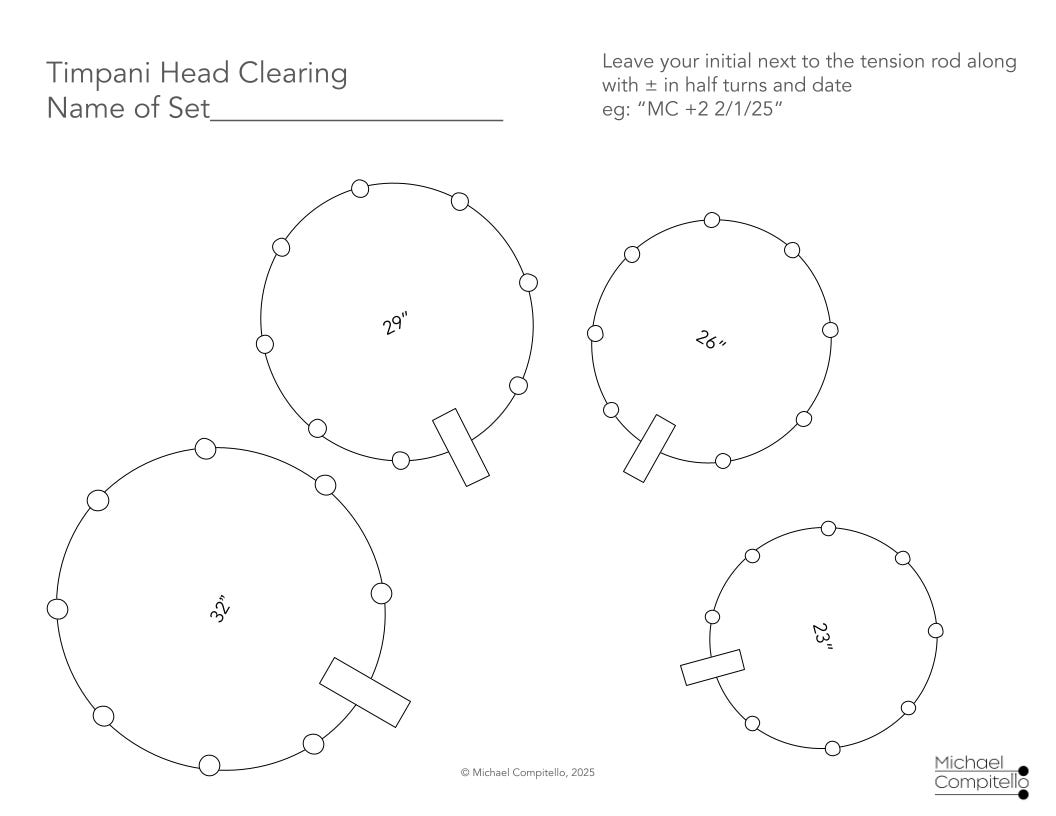

To facilitate this, I made a little diagram of a set of timpani with indications for tension rods. I like to put an initial next to a tension rod with a date, to indicate I made a change on that date. Then, I say “+1, -1, etc.” I only work in half turns: smaller units tend to be less effective.

Happy Practicing!