The Fastest Practice Session Ever

How would you practice if you wanted to spend the least amount of time in the practice room and get the most done?

As a university professor, I spend a lot of time berating my students for not practicing enough, but that’s only part of the story. In reality, I should berate them for not practicing more effectively…or…not berate them at all…?

Learning to learn is the single most essential outcome of studying music at a university. As such, developing effective, flexible, and individualistic practice habits is the quintessential task of the student musician, the most essential ingredient in the pivot from talent to skill that demarcates the professional from the amateur.

I was not an effective practicer while in school, prone to binges on single techniques, long forays into a single action, and hopeless attempts to memorize music too quickly.

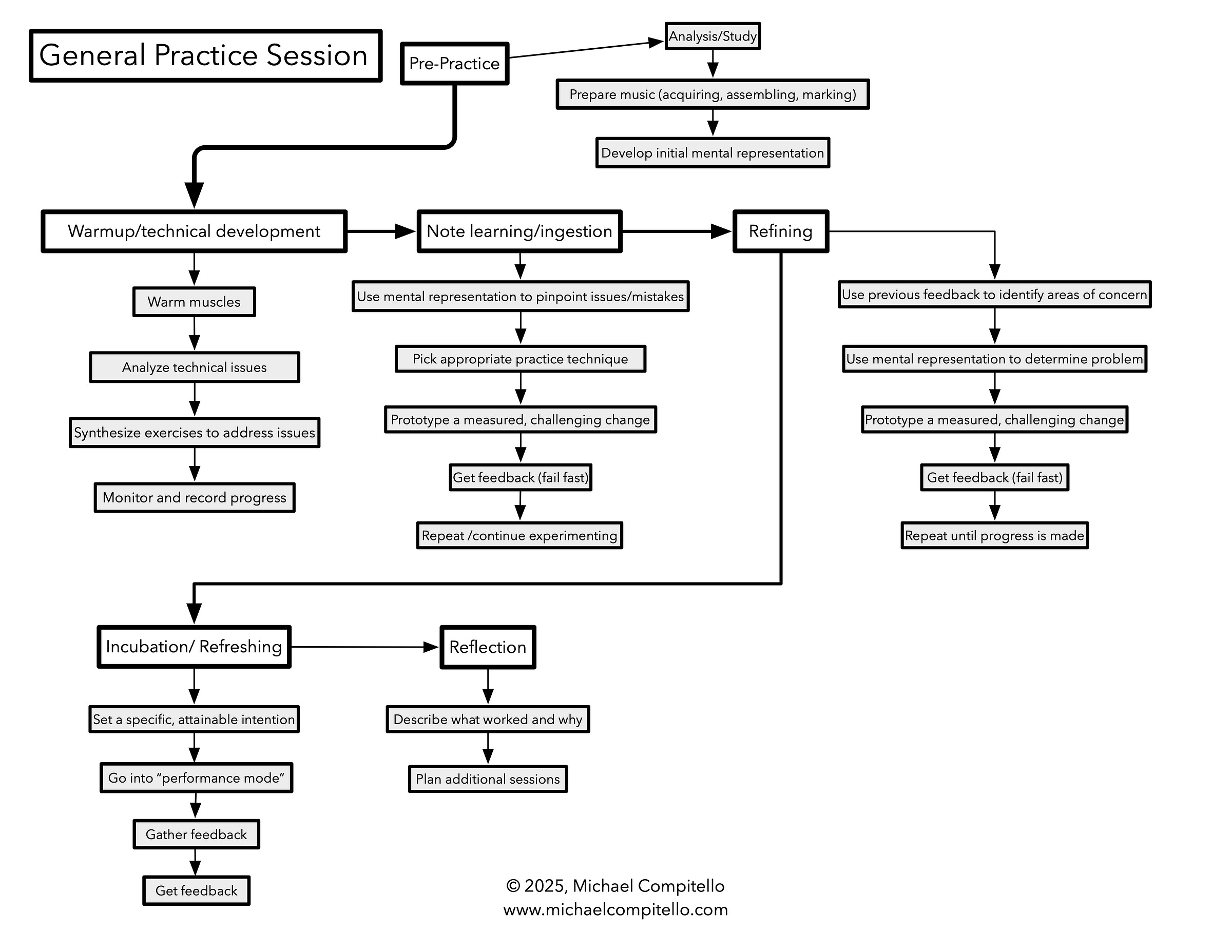

In an effort to not have my students repeat my mistakes, clarify my thoughts on practicing and give my students a framework for effective individualization of complex musical tasks, I made a flow chart, documenting what my research led me to conclude are the most important touch points in each practice session.

This chart lays out the phases of a practice session, and hews to best practices from cognitive neurology (interleaved practice, cognitive interference, deliberate practice, etc). I believe every practice session should include most of, if not all of these categories of activities, for maximal, long-term benefit.

More importantly, it answers the question:

How would you practice if you wanted to spend the least amount of time in the practice room and get the most done?

Pre-Practice: Analysis/score study/framing

Get to know the music you’ll be learning, contextualizing it historically and stylistically while analyzing and characterizing significant moments in the music. You want to be sure that I’m practicing with a musical goal in mind rather than wandering note-by-note through a score.

Then, prepare everything you need to make sure that your time practicing is 100% practicing. Score printing, part preparation, page turn planning, binder making, etc.

Getting Going: warm up, scales, technical development

Like standing in an immersive James Turrell work, our minds and hands need a little bit of time to acclimate to practicing. My goal is to refine my percussive technique, but also to open my ears and keep critical thinking.

Warm your muscles by playing conscientiously and curiously, analyzing technical issues by tinkering, hypothesizing about their origin and experimenting to see what changes make the most impactful sonic results.

Create and play exercises that address these issues. I like to, like Law and Order, rip them from the ‘headlines’ of my repertoire.

Don’t skip this section! Warming up is as much a mental as a physical ritual, and helps get your mind ready to focus.

Finally, do SOMETHING to measure and record your progress. This could be a practice journal. It could be marking something in the music. It could be your memory (not recommended). Keeping track of milestones and benchmarks and challenges gives you valuable information you can incorporate into your next session, so you don’t have to start from square one each time.

Need some warm-up ideas?

Note Learning/Ingestion

I say ingestion here because it’s more specific than learning. Anyone can learn something, but it takes effort to digest information, keep it inside of oneself ready to use at a moment’s notice.

Because of your analysis and study (you have been analyzing the music you’re learning, right?), you already have a strong idea of what you expect the piece to sound like. You have a hypothesis about what you want to do interpretively in the music before you’re learning the notes. This hypothesis or musical thesis will change, of course. But learning and interpreting notes is much easier when the notes are part of sentences and paragraphs and chapters rather than random dots.

As you play a section of the piece, use this sense of what the music “should” be like to pinpoint issues or mistakes—sounds or gestures that deviate from your conception.

Address the problem with an issue-specific tool.

What fills up your toolbox of practice methods? Ideas from creative practice sessions, sounds from mentors or idols, memories from coachings or lessons, inspiration from other artistic disciplines, ideas from scientific research into learning methods, analogies. In short, everything creative or curious that we do.

Don’t confuse this way of practicing with always shooting for the same musical goals. Practicing this way does get you closer to your desired interpretation very quickly. But, paradoxically, asking specific questions of the music at hand and toying around with techniques and musical ideas broadens expands your conception of what a desired interpretation could be. So be specific from step one.

I wrote about some of my favorite practice tools here

Refining

The same, but with both longer spans of music and more refined or detailed sense of what to address.

Record yourself and get feedback from peers to make sure your senses are calibrated to your sound.

Refreshing/Longer Runs/Incubation

This period occupies the LONGEST part of our practice time. Start piecing together the music, section by section, paragraph by paragraph.

You will make different and surprising and delightful new mistakes, so continue the processes from before. Let the music age like a Brunello wine (although maybe not for as long).

Reflection

Learning = Experience + Reflection. So………… reflect! What worked, what didn’t? Be creative and resilient.

Need some help reflecting?

Timing

Except for the incubation, which could take years, this routine takes an hour or less—one Law and Order episode.

In each section of the practice session, we’re harnessing Deliberate Practice and Design Thinking. Ideation, prototyping, failing fast, and iterating new solutions are key steps in musical improvement.

Happy practicing!

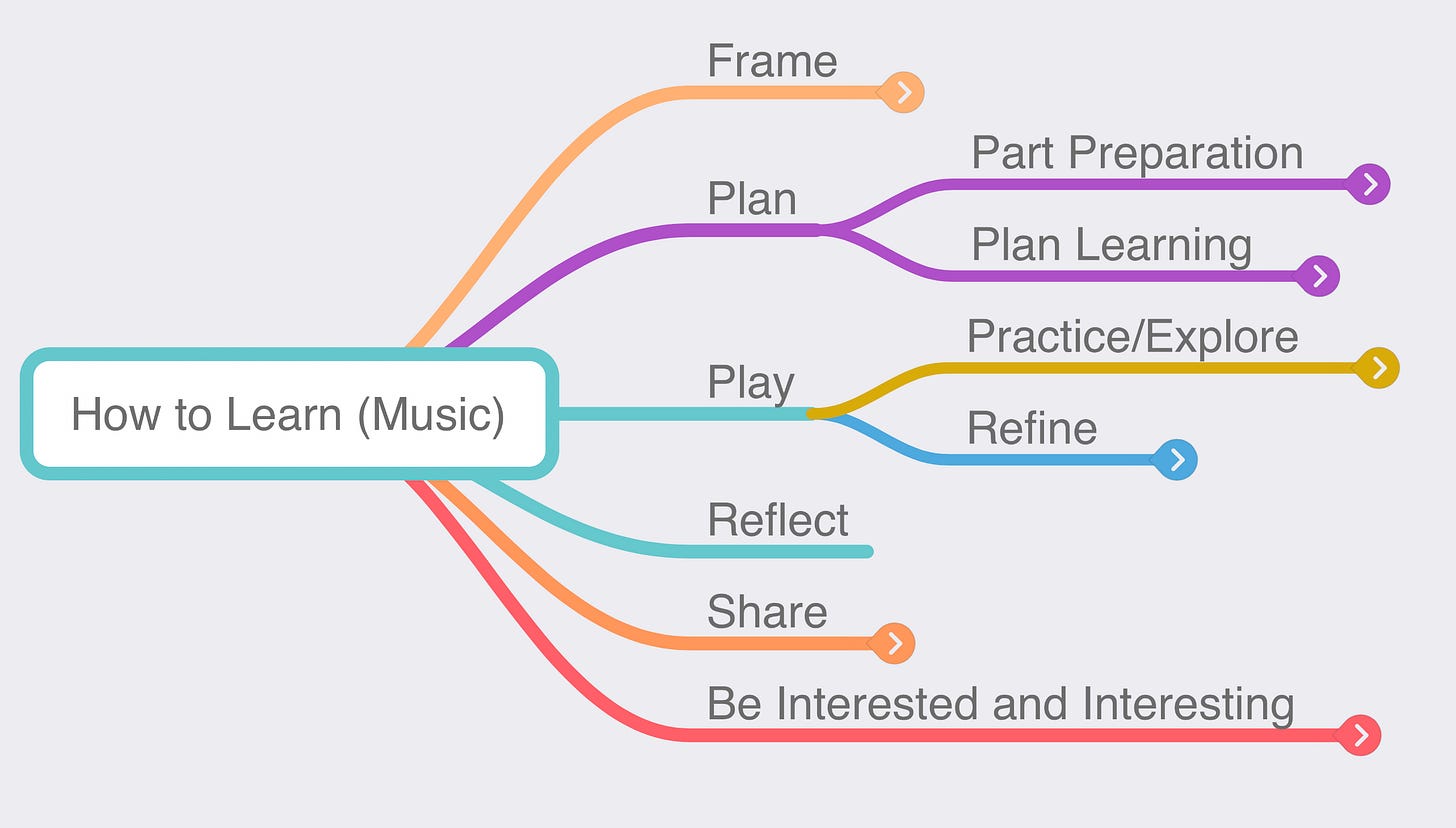

PS: For those of you keeping score, here are my stages in learning music: